By. Mazi. Godson. Azu.

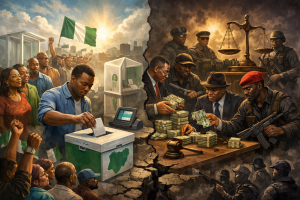

In the wake of former President Donald Trump’s controversial second term, global politics finds itself unsettled not simply because of the extraordinary decisions emanating from Washington per se, but because those actions challenge long-standing assumptions about American primacy and the structure of the international system.

Recent events from U.S. military intervention in Venezuela and threats regarding Greenland and Iran, to an overarching foreign policy dubbed America First have reignited debates over whether the world is stabilizing under one global hegemon, fragmenting into two great power blocs, or entering a more complex, multiplex order.

I. What Is Trumpism in a Geopolitical Context?

At its core, Trumpism and specifically the foreign policy variant shaping U.S. actions intertwines:

• America First nationalism, prioritizing perceived direct U.S. interests above multilateral commitments or normative universalism, and

• a revived willingness to use hard power military force, coercive diplomacy, economic sanctions, and strategic pressure even in ways that clash with international law or established norms.

This combination breaks with the post-World War II liberal international order an era defined by U.S. leadership tied to alliances, international institutions, and a belief that American power could be wielded in service of both national and global stability.

“The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over.”

2025 U.S. National Security Strategy, under Trump’s leadership.

This statement captures a central tension: Trumpism rejects the idea of benevolent global stewardship, replacing it with transactional power politics what some scholars call a new form of competitive global governance where international rules may be selectively upheld, reshaped, or discarded to maximize national advantage.

II. Trumpism in Action: Venezuela, Greenland, and Iran

Venezuela

In 2026, the Trump administration executed a significant military operation to remove Nicolás Maduro from power and install U.S. control as a “transition authority,” emphasizing security and energy stability. This action starkly contrasts with Trump’s earlier anti-intervention rhetoric, sparking debate over whether America really seeks isolation or something closer to neo-imperial hegemony.

Greenland

Trump’s repeated remarks including controversial statements suggesting the U.S. might seize “our” strategic Arctic island rekindled discussions about territorial ambition and realpolitik competition with Russia and China for Arctic influence. While Denmark rebuffed these ideas, the episode widened cracks within NATO and prompted European calls for strategic autonomy.

Iran

The administration’s approach to Iran combines sustained economic pressure (reviving maximum pressure tactics) with occasional threats of force, underscoring a willingness to apply leverage wherever U.S. interests are perceived to be at stake.

Taken together, these incidents highlight an assertive, sometimes unilateral U.S. posture one that seeks to enforce “American interests” rather than uphold collective global norms. Critics argue this risks destabilizing regions and eroding international legal frameworks.

III. Theoretical Lenses: Monopolar, Bipolar, or Multiplex Orders?

To frame these developments, it’s useful to revisit classic international relations (IR) theories:

- Monopolarity

In the aftermath of the Cold War, scholars like Charles Krauthammer posited a unipolar world dominated by the U.S., with unrivaled military and economic reach. Trumpism superficially seems to revive this — asserting U.S. dominance across hemispheres and beyond.

Yet the brutal realities of military overstretch, economic interdependence, and alliance fatigue suggest that unilateral U.S. dominance alone cannot sustain stability indefinitely.

- Bipolarity

A bipolar world dominated by two superpowers characterized much of the 20th century (U.S. vs. USSR). Today, the approximate analogue might be a U.S. bloc versus a rising China (potentially aligned with Russia). China’s growing economic, technological, and military capabilities position it as a serious counterweight, with initiatives like the Belt and Road and advocacy for alternative global governance structures.

However, unlike Cold War bipolarity, current dynamics lack rigid ideological spheres. Many nations resist alignment, pursuing pragmatic engagement with both powers.

- The Emerging Multiplex or “Multipolar plus” Order

Some academics argue we are entering a multiplex order not strictly unipolar or bipolar where multiple centers of influence interact: U.S., China, Russia, the EU, India, and regional coalitions all exert power in distinct arenas. Smaller and mid-sized states increasingly leverage non-alignment and diversified partnerships to navigate pressure from great powers.

This approach resonates with historical cycles: after periods of hegemonic dominance, such as British or American hegemony, the system tends toward more diffuse power structures where no single nation can enforce stability alone.

IV. Historical and Normative Context

The transformation of global order is not unprecedented. The U.S. itself once resisted European imperialism, only to later adopt doctrines like the Monroe Doctrine in the 19th century to assert regional dominance. Today, Trumpism’s “Trump Corollary” explicitly invokes the Monroe legacy — expanding U.S. influence through coercive and strategic means in its hemisphere.

Yet whereas the post-1945 order attempted to embed U.S. power within rules, norms, and institutions, Trumpism often treats such frameworks as obstacles or tools to be reshaped at will. This shift echoes broader debates in international politics: are rules the foundation of order, or mere veneers atop great-power competition?

V. Key Thought Process:

1. Is Trumpism fundamentally about power projection or national self-protection?

Supporters argue it prioritizes U.S. citizens and resists burdensome commitments. Critics see it as a return to “might makes right.”

2. Does Trumpism accelerate multipolarity by weakening U.S. alliances and creating openings for China and Russia?

If so, will a bipolar world emerge de facto, or will power be even more fragmented?

3. Can international institutions survive a systemic shift away from rules-based order?

Or will they evolve into new forms of governance reflecting diverse interests?

4. What role should smaller nations play in shaping a post-American hegemony world order?

Will they unite into coalitions to balance great powers, or continue to align with whichever offers security and economic benefits?

Conclusion

The Trump era’s foreign policy controversies from Venezuela to Greenland to Iran are not isolated incidents but symptoms of deeper, structural shifts in global politics. Whether the emerging world order is best described as monopolar dominance, bipolar rivalry, or a complex multiplex of great powers depends largely on future choices: by the United States, by China and Russia, and by a diverse field of middle and smaller powers asserting their agency.

One thing is clear: the era of unquestioned U.S. primacy defined by broad alliances and multilateral norms is under intense pressure. The debate now is whether the next architecture will be dominated by two titans, many competing centers, or a reconfigured interplay of cooperation and competition.

Godson is a based International Relations and Politics Expert. Director CM Centre for Leadership and Good Governance UK.