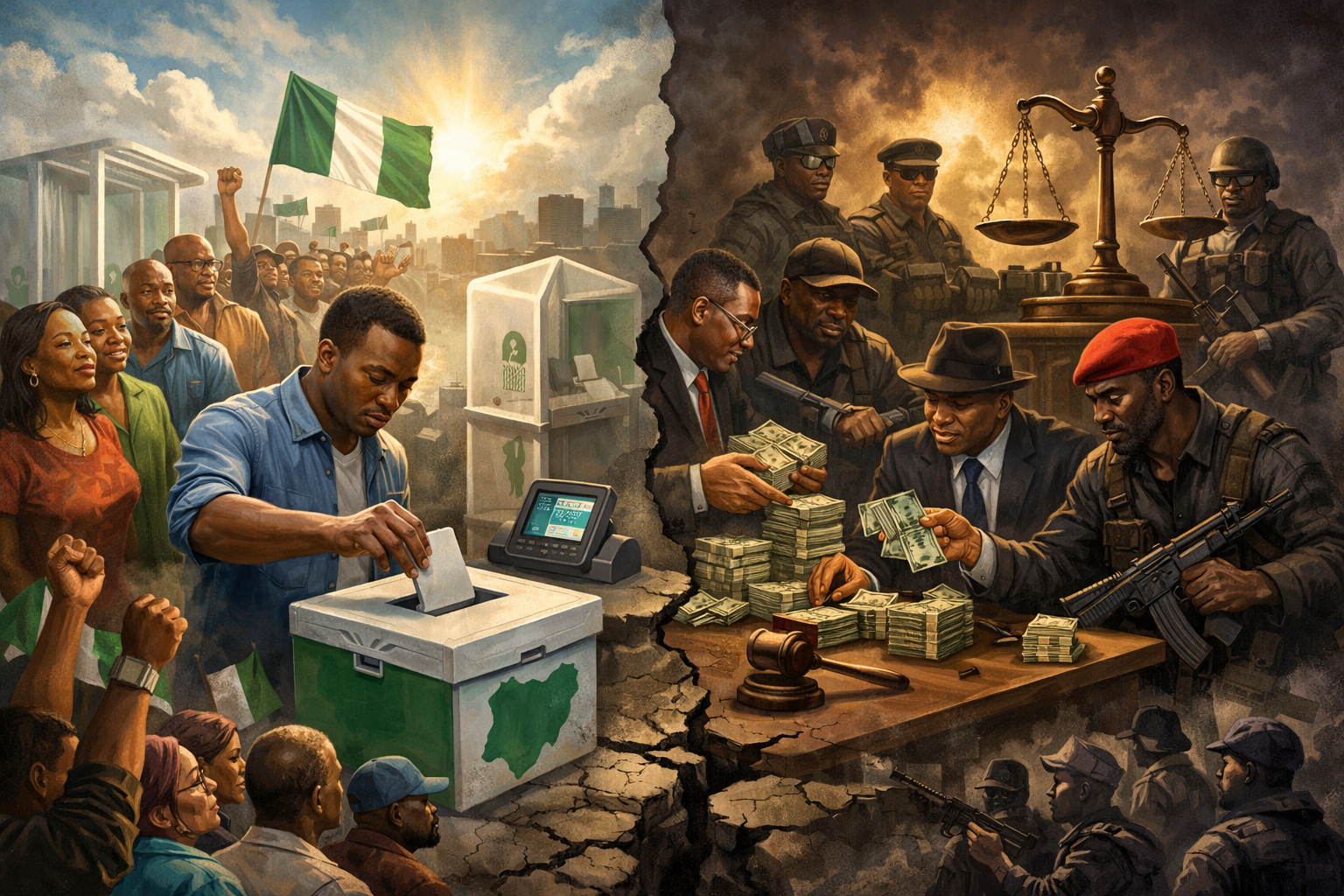

At the heart of democracy lies a simple promise: that the will of the people, freely expressed through elections, determines who governs. In Nigeria, however, this promise has remained fragile and contested. Across electoral cycles, citizens have repeatedly questioned whether elections reflect popular choice or merely the preferences of political elites, enforced through money, institutions, and coercive power.

The persistent tension between the people’s vote and the politicians’ vote raises a fundamental question for Africa’s largest democracy: will Nigerians ever see elections where votes genuinely count? As the country approaches off-season elections in 2026 and the pivotal 2027 general elections, this question has never been more urgent. Historical Roots of Electoral Distrust: Nigeria’s electoral credibility crisis is not new.

From the flawed elections of the First Republic (1960–1966) to the violent and manipulated polls of the Second Republic (1979–1983), elections have often served as triggers for instability rather than instruments of democratic consolidation. The collapse of civilian governments and prolonged military rule entrenched a political culture where power was seized, not earned. The June 12, 1993 presidential election remains a watershed moment.

Widely adjudged as Nigeria’s freest and fairest election, its annulment by the military regime shattered public trust and reinforced the belief that even when citizens vote correctly, entrenched power can override the outcome. Since the return to civil rule in 1999, Nigeria’s Fourth Republic has conducted multiple elections, yet accusations of rigging, vote buying, violence, judicial manipulation, and institutional compromise have persisted. Elections became routine, but electoral legitimacy remained elusive.

Vote Buying, Manipulation, and the Commodification of Democracy: One of the most corrosive features of Nigeria’s electoral system today is vote buying. Elections have increasingly become market transactions where votes are exchanged for cash, food items, or promises of patronage. Poverty, unemployment, and weak civic education have made large segments of the electorate vulnerable to inducement.

Vote buying does not merely corrupt voters; it delegitimizes governance itself. Leaders who purchase mandates often feel little obligation to govern responsibly. Despite the Electoral Act (2022) criminalising vote trading, enforcement remains weak, prosecutions are rare, and political actors operate with impunity.

Beyond vote buying lies a broader ecosystem of electoral manipulation that includes falsification of results during collation, intimidation by political thugs and compromised security agents, logistical failures exploited to suppress turnout, and collusion by compromised electoral officials. These practices ensure that elections are often decided after voting, not by it. Party Decamping and the Betrayal of Voter Choice: Another structural distortion of the people’s vote is party defection (decamping).

Nigerian politicians frequently switch parties before or after elections without consulting voters. This practice undermines ideology, weakens party systems, and effectively nullifies the mandate voters thought they gave. When governors, legislators, or senior officials defect en masse, voters are left disenfranchised and represented by parties they did not vote for.

The absence of strong legal sanctions against opportunistic defections has turned Nigerian politics into a game of survival, not service. The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) occupies a central role in Nigeria’s democratic experiment. Over time, it has introduced reforms aimed at improving transparency, most notably technological innovations.

In the 2015 presidential election, the introduction of Smart Card Readers significantly reduced multiple voting and contributed to the historic defeat of an incumbent president. The peaceful concession of defeat marked a rare moment of democratic optimism and suggested that institutional reform could make votes count. In the 2023 presidential election, INEC expanded reforms through the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) and the INEC Result Viewing Portal (IReV), intended to enable real-time result transmission.

However, technical failures, delays, and inconsistencies in result uploads severely undermined public confidence. What was meant to deepen transparency instead intensified suspicion and post-election litigation. The lesson from 2015 to 2023 is clear: technology helps, but technology alone cannot save elections without institutional integrity and political will.

Security forces are meant to protect voters and electoral processes. Yet in many elections, they are perceived as partisan actors who selectively enforce laws or intimidate opponents. This erodes trust and reinforces the belief that the state apparatus serves political elites rather than citizens.

The judiciary is the final arbiter of electoral disputes. However, inconsistent judgments, prolonged litigation, and allegations of political influence have weakened confidence in electoral justice. When courts appear to validate disputed outcomes, citizens conclude that elections are merely preludes to judicial bargaining.

Comparative experiences from other transitioning democracies offer valuable lessons. In countries such as Uruguay, electoral commissions are constitutionally entrenched and insulated from executive interference, and Nigeria must strengthen INEC’s independence financially, administratively, and operationally. Best practices also demand mandatory real-time transmission of polling-unit results, open access to election data for civil society and media, and independent audits of electoral technology.

Nigeria’s BVAS and IReV systems should be legally reinforced, independently audited, and made fully transparent. Countries like Papua New Guinea have attempted to curb defections through party-integrity laws, and Nigeria needs constitutional or legislative reforms requiring elected officials who defect to seek a fresh mandate. Jurisdictions such as Kenya have strengthened electoral dispute resolution through specialized judicial mechanisms, and Nigeria would benefit from independent electoral tribunals with strict timelines and transparent procedures.

Kenya’s Uchaguzi platform demonstrates how citizen-driven election monitoring can enhance accountability, and sustained voter education and digital reporting platforms can reduce vote buying and expose malpractice in real time. The answer is yes, but only conditionally. Nigeria’s democratic future depends on genuine electoral and judicial reform, enforcement of laws against vote buying and manipulation, institutional independence backed by political courage, and an empowered, vigilant, and informed citizenry.

The contrast between 2015’s cautious optimism and 2023’s contested legitimacy shows that progress is reversible. Without deeper reforms, elections risk becoming rituals that legitimise elite bargains rather than expressions of popular will. Nigeria does not suffer from a lack of elections; it suffers from a deficit of electoral justice.

Until votes are counted transparently, protected by institutions, upheld by courts, and respected by political actors, democracy will remain incomplete. The struggle between the people’s vote and the politicians’ vote is ultimately a struggle over who owns sovereignty. If Nigeria is to consolidate democracy by 2027 and beyond, the state must decisively shift power back to citizens, not in rhetoric, but in practice.

Only then will the people’s vote truly count. By Mazi Godson Azu, Director, CM Centre for Leadership and Good Governance (UK), UK-based International Relations and Politics Expert. The Convener of Annual London Political Summit and Awards.